Let me start with the before. Before my world split in two, I was a woman who defined herself by her productivity. I was a Business Development Specialist for start-ups, a title that conjures images of sleek laptops, ambitious pitch decks, and the palpable thrill of building something from nothing. I was a wife, a mother and by all standard metrics, a successful adult.

Then my daughter was stillborn

The aftershock of that event didn’t just change my life; it vaporised the person I had been. Grief is not a state of being; it is a full-time occupation with brutal, unending hours. You are dying, drowning, screaming your heart has left your chest and fallen to the floor. That other person was replaced by a new person; the Professional Griever.

And in my desperation, I did what any rational, broken person would do: I begged for a manual. I am a Christian woman, so I took my pleas directly to the top, to God, demanding answers with frantic and furious logic. The silence that answered wasn’t divine; it was deafening.

A clandestine network of loss

Then, something happened. Women began to emerge from the periphery of my life, stepping out of the shadows of their own seemingly intact lives to whisper their secrets. It was a clandestine network of loss, a secret club with the worst membership fee imaginable. One by one, they confessed. Me too. I lost one. I lost two.

To each of them, I posed my desperate, fundamental question, the only one that mattered in the rubble of my new existence: “What next? What did you do? What is step one?”

Their answer was a universal, maddening shrug of the soul. A phrase so inadequate it felt like a physical insult: “You just… move on.”

Move on? Moving on is for bad breakups and failed start-ups. It is not for the death of a child. That loss is not a setback; it is a permanent, fundamental subtraction from the universe of yourself. A limb has been amputated. You don’t “move on” from that. You learn to walk with a phantom ache, a limp that forever alters your gait. The notion of “moving on” is a lie we tell the grieving to make the witnesses of grief more comfortable.

Everyone, in the raw immediacy of loss, wants to know why. “Why me? Why my child?” I asked it for so many hours on my knees. But I’ve come to believe “why” is the wrong question, it is a black hole that sucks you into a vortex of unanswerable despair. The real, practical, gut-wrenching question is, “What now?” What do I do with this pain today? How do I get through the next hour? The answer, I discovered, is not to numb it or outrun it, but to sit in the center of the storm and feel every excruciating grain of it. The pain isn’t the obstacle; it is the path itself. It is the only way through.

You don’t “get over it.”

And let us be brutally clear: you don’t “get over it.” You don’t reach a finish line of healed-ness. This is a permanent residency. My father recently informed me, with the casualness of someone noting a change in the weather, that my mother had suffered three miscarriages. It was a throwaway line for him, but for me, it was a key that unlocked decades of my mother’s behavior, the unexplained sadness that would settle over her for weeks, the way she’d sometimes look at me and my siblings with a ferocity that bordered on anguish.

My cousin still marks the birthdays of the baby she lost over a decade ago, speaking aloud the age the child would have been. She isn’t stuck; she is faithful. We are a vast, silent sisterhood of the walking wounded, pretending we are fine because our culture treats pregnancy loss like a social gaffe, a deeply unfortunate, slightly embarrassing event that should not be mentioned in polite company.

Stigma and misogyny

In our societal narrative, pregnancy is a woman’s final exam, her biological and spiritual purpose. A miscarriage is treated as, a failure, and you are handed a report card of shame, guilt, and insecurity. Recurrent loss is not viewed as the complex medical condition it is; but rather as a curse. A divine punishment for some unnamed sin. I have seen this belief poison marriages from the inside out, with men literally trading in their “defective” wives for newer, more fertile models. I have heard the whispers at family gatherings and in market stalls: She must have been promiscuous. There is a curse on that family. We are forced to bury our babies and then immediately bury our grief under a mountain of ancient superstition and blatant, ugly misogyny. We are grieving, and simultaneously tasked with managing the discomfort of everyone around us.

What shocks me is that even if this is happening more we are doing pathetically, scandalously little about it. As women, we have been sold a powerful lie; build your career first, secure your independence, and the babies will come later. While I am all for this female empowerment, our wombs, our ovaries, didn’t get the memo. They are governed by the merciless, unforgiving logic of biology. The chance of miscarriage doesn’t care about your corner office. It is a brutal, ascending scale: 15% at age 20, a significant jump to 22% at 35, and a catastrophic 70% by 45. We are not giving young women the full, unvarnished truth they need to make informed choices. We are selling them a fantasy of endless time, and the price is paid in lost children and shattered hearts.

Policies

And our policies? Our national response to this epidemic of loss? They are a sick, bureaucratic joke written by people who have never had to choose between returning to work with milk-stained shirts for a baby who isn’t there or losing their job. In Uganda, the law grants a woman a grand total of four weeks of compulsory leave after a miscarriage. Let me repeat that; the same four weeks she would get after delivering a living, breathing child. Let that breathtaking institutional obscenity sink in. Four days for a grieving father to hold his weeping wife and try to piece together the fragments of their world. This is not policy; it is institutionalized cruelty. It is a declaration that a woman’s physical and emotional trauma, the death of her hoped-for child, is a logistical inconvenience to be managed and minimized.

The infrastructure is a sick joke, too. We have three, three! Neonatal intensive care units in this entire country. Three. We treat reproductive health like a dirty secret, refusing to teach comprehensively about infertility until it becomes a devastating personal crisis for countless women who believed the myth of their own endless fertility.

This toxic combination of silence, stigma, and systemic neglect is why I finally stopped being polite. I stopped accepting the shrugs and the “moving on.” I started talking. Loudly. Inappropriately. I said the words “stillbirth” and “miscarriage” in conversations where you are supposed to talk about the weather. And one woman, hearing me, would refer another, who would then refer another. I looked up one day and realized I had become an accidental, untrained grief counselor, a central node in a vast, humming network of pain.

So I did what any frustrated former business developer would do: I built a better product. I built a platform called Vessel Is Me because the government wouldn’t. Because the healthcare system couldn’t. We offer what they don’t; real, tangible perinatal loss care, physical and virtual support groups, a place where you can say your child’s name without making anyone uncomfortable. I enlisted one of the country’s few professional grief counselors because women shouldn’t have to rely on the amateur guidance of other broken-hearted women like me, no matter how well-intentioned.

So here is my unsolicited, unfiltered advice. If you are over 35 and want a family, educate yourself. Treat your pregnancy like the high-risk miracle it is. Be paranoid. Go to the doctor too often. Advocate for yourself with the fury of a mother whose child’s life depends on it, because it does. And if it happens, when it happens, to so many of us, talk about it. Scream it from the rooftops. Your story is not your shame; it is your power. We will talk about our dead babies, we will say their names, we will share our rage and our pain, until the stigma is ashes in our mouths.

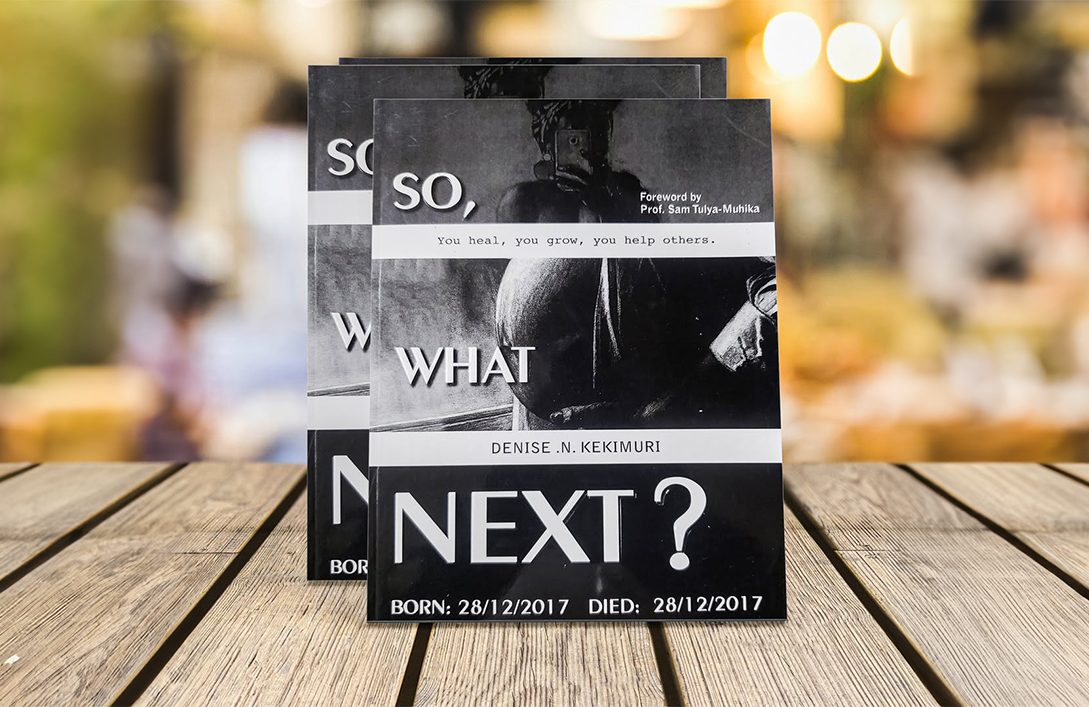

My book, So, What Next?, is not a gentle inspiration pamphlet. It is a battle cry born from the worst day of my life. It is the raw, ugly, inconvenient truth spilled onto the page. Because the only way to change a culture that forces women to suffer in dignified silence is to be undignified. To be loud. To make them so uncomfortable that they have no choice but to finally, finally listen.

Denise Kekimuri is a reproductive health advocate and founder of Vessel Is Me